Machine Learning Meets Radio: Can AI Improve Channel Estimation in BPSK Systems?

-

Posted by

Red Pitaya Technical Editorial Team

, February 18, 2026

Red Pitaya Technical Editorial Team

, February 18, 2026

Machine learning is transforming wireless communications, but can neural networks really outperform classical signal processing? Two electrical engineering students at Southern Methodist University used software-defined radio (SDR) platforms to find out, building a complete digital communications system to test AI-based channel estimation against traditional methods.

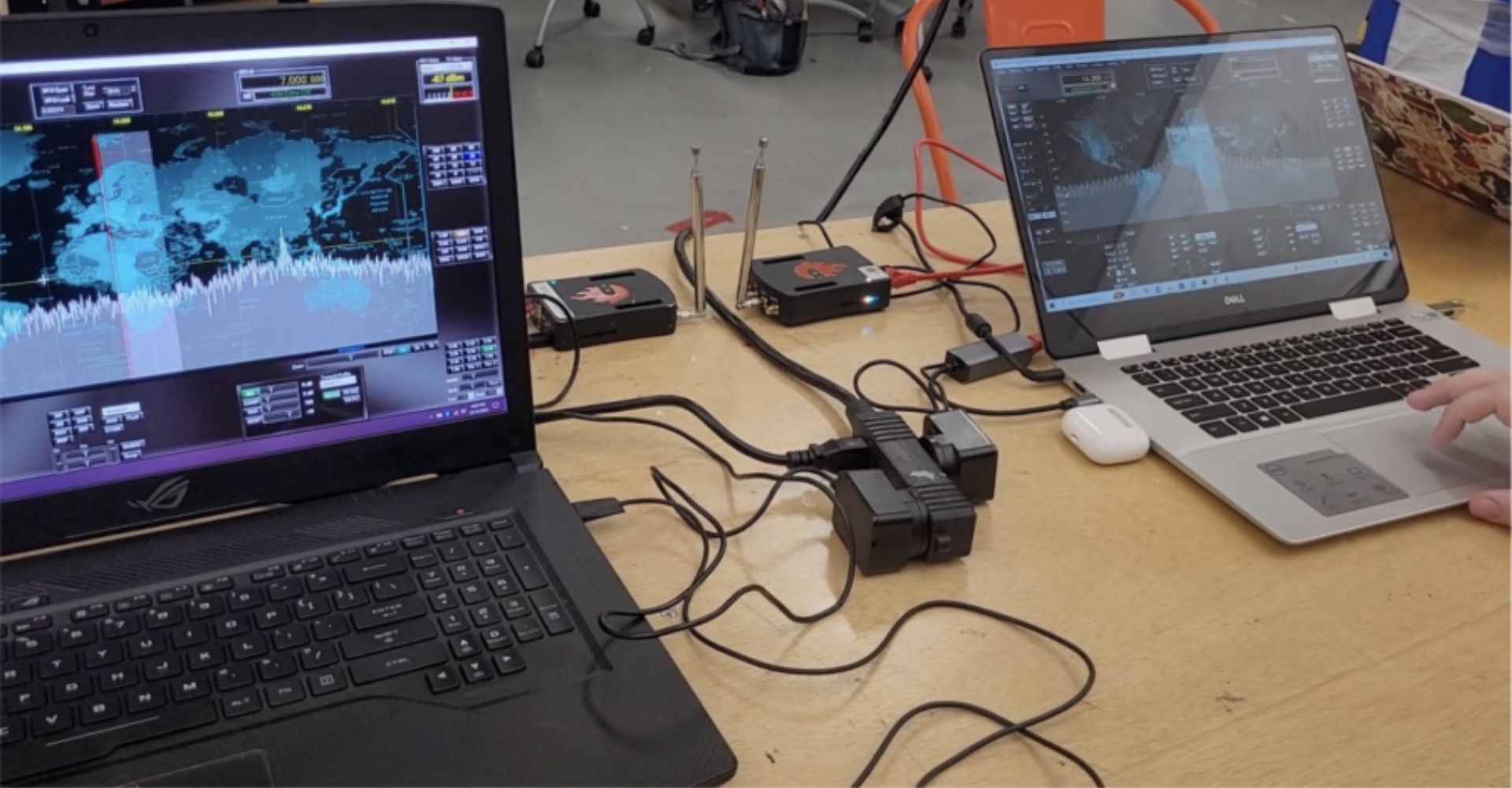

Communication systems depend on knowing the channel: how signals change as they travel through the air. Get it wrong, and your decoded bits turn to garbage. Get it right, and you can pull clean data from noisy signals. Using two Red Pitaya STEMlab boards as affordable SDRs, Aiden Pagiotas and Jackson Scott Reed created a hands-on research platform to explore whether machine learning could improve receiver performance in real-world conditions. The project served as their praxis for Adaptive Algorithms in Machine Learning.

Channel State Estimation in Digital Communications: The Fundamental Challenge

Every digital communication receiver faces the same challenge: the transmitted signal arrives corrupted by noise, fading, and interference. To decode it correctly, the receiver needs accurate Channel State Information (CSI), essentially a mathematical description of how the channel affected the signal.

Classical receivers estimate CSI using known pilot symbols scattered throughout the transmission. While this works well under ideal conditions, performance can degrade when channels become noisy, time-varying, or violate the receiver's assumptions.

They wanted to know: could a simple multilayer perceptron (MLP) learn to estimate CSI from raw baseband samples? And more importantly, would machine-learned CSI improve decoding performance?

Building a Software-Defined Radio Test System with Red Pitaya SDRs

They configured two Red Pitaya STEMlab 125-10 boards as software-defined radios. One acted as transmitter, the other as receiver, communicating via SMA antennas to create a controlled RF channel.

The communication channel used:

- BPSK modulation (Binary Phase-Shift Keying)

- Rate-1/2 convolutional encoding for error correction

- Viterbi decoding at the receiver

- Pilot-based synchronization

Using PowerSDR Charly 25 HAMLab STEMlab Edition, they transmitted waveforms over the noisy RF channel and captured the received baseband samples as WAV files. These recordings became training data: half a million carefully selected samples representing diverse channel conditions, with varying transmission distances and powers.

Designing a Neural Network for Wireless Channel Estimation

They developed an MLP in Python designed to predict complex channel coefficients from:

- Raw I/Q baseband samples

- System metadata (symbol timing, modulation parameters)

- Local signal history

- 15 training epochs with early stopping

- Batch sizes of 512 samples

- Mean squared error loss on channel magnitude and phase

After experimenting with architectures, they settled on:

The network would compete against classical pilot-based estimation. Performance metric: bit error rate after Viterbi decoding.

Machine Learning Data Management: Handling Massive SDR Datasets

Their first attempt used 192 kHz sampling over 30-second recordings, generating nearly 2 billion training samples. Even a high-performance computer using modern GPUs choked on this dataset.

Solution: Strategic sampling. By extracting 500,000 samples from different recording segments without overlap, they were able to maintain sample diversity while achieving computational feasibility. MATLAB handled the signal processing; Python trained the model.

Comparison of loss curves before (left) and after (right) reducing training data size, increasing batch size, and implementing train/validation split

Comparison of loss curves before (left) and after (right) reducing training data size, increasing batch size, and implementing train/validation split

Carrier Frequency Offset: When Neural Networks Meet RF Impairments

After making adjustments to the training process, it looked like things were smooth sailing: training converged nicely. Loss decreased, validation metrics looked good. But when comparing decoded bits, disaster struck. The ML-based receiver produced bit error rates several orders of magnitude worse than the classical approach.

Looking at the phase traces revealed the issue: the MLP's phase estimates drifted wildly from the classical predictions, with unexplained spikes of one to three radians.

The culprit? Carrier frequency offset (CFO), a systematic frequency mismatch between transmitter and receiver that creates continuous phase rotation. While classical receivers explicitly handle CFO through established compensation techniques, the neural network had no mechanism to account for this global impairment.

Hybrid Approach: Combining Classical DSP with Machine Learning

Machine learning alone wasn't enough. They needed to incorporate classical signal processing.

They explicitly estimated CFO before training:

- Computed pilot-based channel estimates

- Unwrapped the phase over time

- Modelled phase as a linear function of the symbol index

- Least-squares fit reveals CFO slope (radians/symbol)

- Compensate the received signal before ML processing

To improve robustness, they performed slope estimation using only high-magnitude pilot samples, filtering out noisy observations that could skew results.

Performance Comparison: ML vs Classical Channel Estimation

Even with CFO compensation, residual phase detrending, and careful preprocessing, their ML-based receiver couldn't match classical performance. While classical decoding sat around a BER of 0.00041, the lowest they were able to get the ML-aided approach over successive iterations was 0.03.

The neural network learned local signal features well. Magnitude tracking was reasonable, and training metrics suggested the model was capturing useful patterns. But it struggled with global, systematic impairments that are fundamental to radio channels.

What they learned:

- Domain knowledge matters. Classical signal processing techniques evolved specifically to handle systematic impairments like frequency offset and timing mismatch.

- Not all problems are ML problems. Some systematic effects are better handled by analytical models than learned patterns.

- Hybrid approaches may be key. Combining ML pattern recognition with classical signal processing primitives could leverage both strengths.

- Architectures that explicitly model frequency offset

- Hybrid receivers using ML for pattern recognition and classical techniques for systematic corrections

- Transfer learning across different channel conditions

- Adversarial training to handle worst-case impairments

The Future of AI in Wireless Communications Engineering

This project revealed important truths about machine learning in communications. While neural networks excel at learning complex patterns from data, competitive performance in real systems often requires the same classical corrections that traditional receivers use.

The question isn't "ML vs. classical." It's "how do we best combine them?" Future work might explore:

- Architectures that explicitly model frequency offset

- Hybrid receivers using ML for pattern recognition and classical techniques for systematic corrections

- Transfer learning across different channel conditions

- Adversarial training to handle worst-case impairments

Open-Source SDR Platforms for Communications Research and Education

None of this exploration would have been possible without Red Pitaya's flexibility. The platform enabled:

- High-quality baseband capture for ML training

- Controlled waveform transmission for repeatable experiments

- Seamless Python/MATLAB integration for rapid prototyping

- Affordable dual-SDR setup impossible with commercial equipment

For students tackling communications projects, having two synchronized SDRs with full I/Q access and software control opens possibilities that bench equipment simply can't match.

What's Next?

These two are graduating this spring, but the questions remain open. Could different architectures work better? What about end-to-end learning where the network learns both encoding and decoding? How would this approach scale to OFDM or MIMO systems?

For students interested in communications and machine learning, this intersection offers rich territory for exploration—and Red Pitaya provides the tools to do it affordably.

Technical Specifications

Hardware:

- 2× Red Pitaya STEMlab 125-10

- SMA antenna for wireless communication

- USB and Ethernet connectivity

Software Stack:

- PowerSDR Charly 25 HAMLab STEMlab Edition

- Python (TensorFlow for MLP)

- MATLAB (signal processing & analysis)

System Parameters:

- BPSK modulation

- 192 kHz sample rate (decimated for training)

- Rate-1/2 convolutional coding

- Pilot-based synchronization

- Soft-decision Viterbi decoding

About the Authors

Aiden Pagiotas and Jackson Scott Reed are senior Electrical and Computer Engineering students at Southern Methodist University, graduating in Spring 2026. This project was completed as part of their Adaptive Algorithms for Machine Learning course.

Connect with the team:

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can machine learning improve wireless communication receivers? A: While ML shows promise for specific tasks like noise pattern recognition, this student project demonstrated that classical signal processing techniques still outperform neural networks for systematic impairments like carrier frequency offset in BPSK systems.

Q: What is software-defined radio (SDR)? A: SDR uses programmable hardware to implement radio functions in software rather than fixed circuits, enabling flexible experimentation with different modulation schemes and signal processing algorithms.

Q: Why use Red Pitaya for communications engineering education? A: Red Pitaya STEMlab provides affordable, open-source SDR capabilities with full I/Q access, making advanced wireless communications experiments accessible to students without expensive lab equipment.

Q: What programming skills are needed for SDR projects? A: This project used Python for machine learning (TensorFlow), MATLAB for signal processing, and PowerSDR software for SDR control—typical tools in communications engineering education.

About the Red Pitaya Team

The Red Pitaya Technical Editorial Team is a cross-functional group of technical communicators and product specialists. By synthesizing insights from our hardware developers and global research partners, we provide verified, high-value content that bridges the gap between open-source innovation and industrial-grade precision.

Our mission is to make advanced instrumentation accessible to engineers, researchers, and educators worldwide.